🌏 A tour of China's electrostate

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs

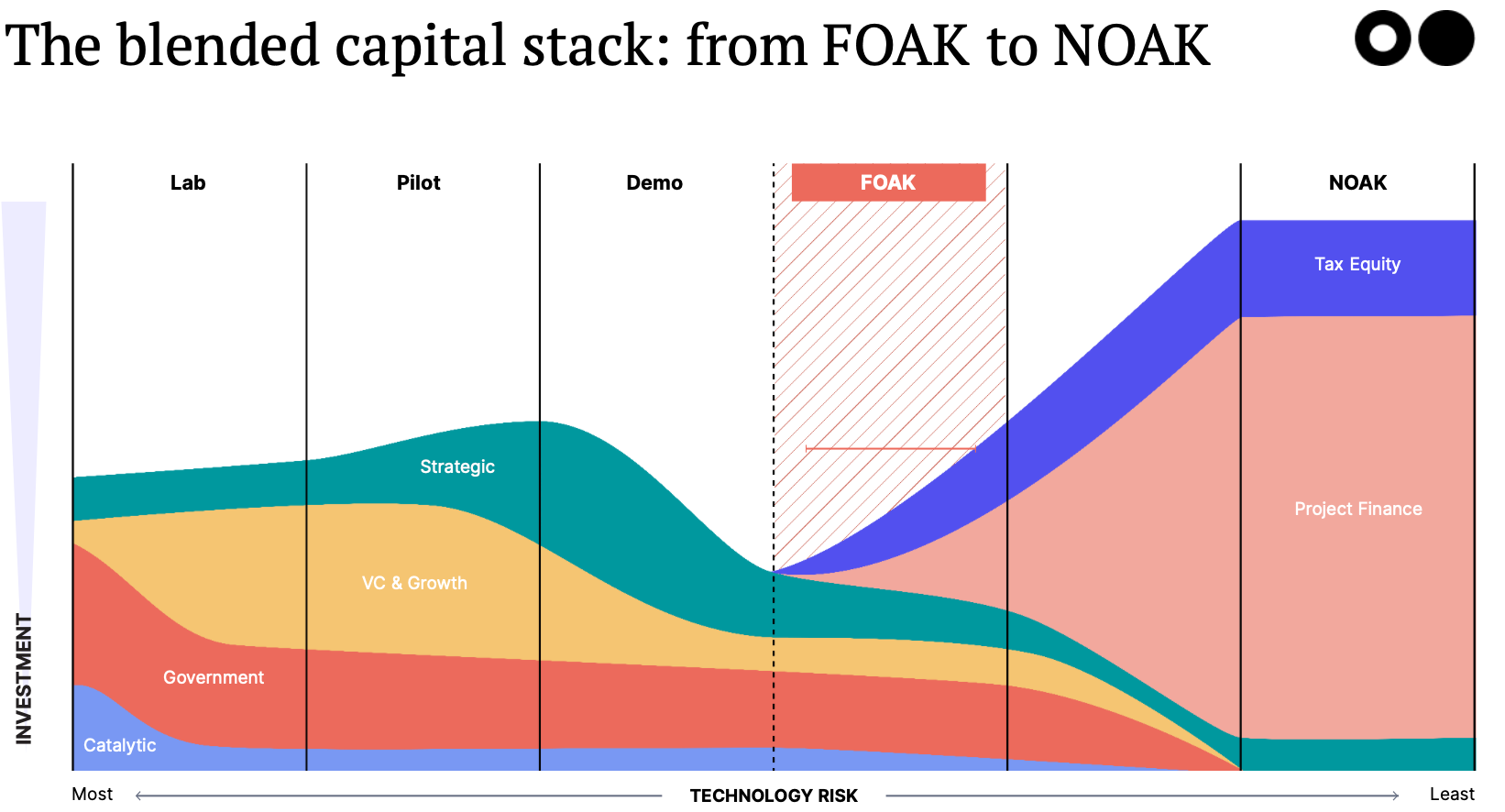

Thought we were done with this FOAK series? NOAK! Think again. Before we set you off on your merry deployment way, we’ve got one more project scaling step left from Pilot to FOAK, now to NOAK and beyond.

At FOAK, definitionally something must be novel — otherwise, it wouldn't be a First-of-a-kind. That novelty can come in the form of the technology, the business model, the application, the geography, or a plethora of other knowns and unknowns. Each dimension of novelty adds risk, and the riskier, the higher the cost of capital. But these obstacles aren’t impassable, nor is the journey impossible with the right FOAK financing and the right people, pilots, plan, and partners.

Post-FOAK, what’s to show for it? Tens of thousands of hours of consistent operations and product creation. An established track record that can be diligenced, robust partnerships, and proven profitable unit economics. The remaining risks are those common to all new projects; macroeconomic conditions, regulatory changes, suppliers or offtakers going bust, acts of God, etc.

If FOAK crosses the “Valley of Death”, NOAK bridges projects to repeatable bankability. Nth-of-a-kind projects that are de-risked at scale are rewarded with access to deep pools of comparatively cheap capital. This may be from institutional infrastructure investors like Antin, Macquarie, GIC, Generate, and Brookfield’s Energy Transition Fund, as well as, ideally, global asset managers like Carlyle and mega-pensions like CPP Investments. By NOAK, it becomes possible to raise debt (and other credit vehicles) from conservative project finance banks, like MUFG or Santander. By this stage the gates of non-dilutive capital have opened — key to the FOAK-to-NOAK transition. Projects are no longer built with equity, but ideally ~80% debt. Finally, growth doesn't come at the price of dilution.

A NOAK investor speaks a different language than the world of VC: Rather than looking at the growth potential of the company, they’re looking for proof that projects are delivered and operate as intended. Consistently. Again and again. Until underwriting becomes beautifully boring.

This post outlines expectations for companies setting out on the journey from FOAK to NOAK, and some anticipated challenges. Primarily, we explore five areas where change should be expected:

Going for NOAK!

At FOAK: The goal is to prove that the products/molecules/electrons made at small scale can be made at commercial scale, from reliable supply chains, and sold and delivered to a market that wants them. Technology risk is often talked about first, but equally important is developing creditworthy commercial agreements and demonstrating product market fit. Scale is moot if no one wants it.

At NOAK: The expectation isn’t just that it’s worked once, it's that it works reliably in different situations. While FOAK just proves it can work, NOAK requires showing it always works, so much so that it’s “boring.” Easy to build, easy to finance. A fully de-risked project model is when all you have to do is rinse and repeat.

What to watch:

At FOAK: As we covered in our last post, financing FOAK is hard. The combination of high risk and high capital requirements means FOAK financing falls between growth equity and project finance. Typically FOAKs, as well as second-of-a-kind (SOAK), and third-of-a-kind (THOAK) projects, blend several sources of capital.

At NOAK: As indicated in the chart below, by NOAK project finance dominates, along with support from tax equity in the US and some investment from strategics.

What to watch:

The chart suggests how the blend and availability of capital changes over time. The split between the colors at each project stage represents which types of capital are most available at which stage, while the total height of the stack at each stage indicates the relative availability of capital; the higher it is, the easier it's likely to be to access.

As a refresher, “catalytic” refers to patient, risk-tolerant, concessionary, and flexible investment capital, while “VC & Growth” refers to venture capital (investing in early-stage companies) and growth equity (funds investing in growth-stage climate tech companies or acquiring controlling stakes in climate tech companies). Strategics are corporates, like O&G or industrials, scaling up direct investment. Government includes non-dilutive government grants and loans, typically from the DOE in the US. With tax equity, tax credits can be monetized as an offset to the taxpayer’s tax liability. Project finance consists of a number of different types of capital, including debt (maybe 60-80%) and equity (20-40%).

At FOAK: The project may technically be run by a subsidiary of the company though a special purpose vehicle (SPV) for the project, or in rare cases, developed directly by the topco. Either way, it’ll likely be topco staff who are developing and then operating the project.

At NOAK: Before you know it, your tech-led startup has grown up. A much wider range of structures and models become possible, such as:

What to watch:

At FOAK: FOAKs generally don't make eye-popping profits for the topco, but the strategy of going from FOAK to NOAK is to be “long-term greedy.” Building early projects may require concessionary deals with investors or strategics. This might mean:

At NOAK: As we get to “boring and bankable,” everybody eats. With proof of commercial model, greater volume, and plenty of existing successful plants to point to, it should be easier to attract favorable terms with offtakers and suppliers. As well as being possible, it may also be necessary. Infra investors are specifically looking for ironclad contracts to protect against volume and commodity risks.

What to watch:

At FOAK: Stepping up to commercial scale sometimes necessitates doing things differently. That might mean changing processes so it doesn't require the lead engineer to be there at all times, or changing inputs because it turns out using a certain material just isn’t cost-effective at scale. From FOAK to SOAK to THOAK, development processes may evolve with learnings from each project applied to the next, hopefully, reducing costs and time frames as you go.

At NOAK: Processes are tried and tested. There are training courses in how to set up and operate your facilities. Crucially, the facilities being built, or products or output produced (depending on your tech) are moving towards modularity and standardization. Modularity enables meeting a range of size requirements by adding units together. It also allows focus on a smaller number of products, ideally one, which in turn sharpens the learning curve, driving down costs faster. Standardization involves producing units according to established norms, ensuring compatibility with other technologies and products, thereby simplifying usage for clients and boosting demand.

What to watch:

FOAK ➡️ NOAK

FOAK Heros: Case studies in NOAKs

Case Study 1 - Archaea Energy

Founded in 2018, Archaea Energy rapidly grew to become one of the largest renewable natural gas (RNG) producers in the US, going public via SPAC in 2021 before being bought out by BP in 2022. While the underlying technology was by no means novel, at the outset their competitors business model was to sell to a transportation credits spot market, Arachea’s novelty came by focusing on providing green gas to companies with public net zero targets. The issue was that the spot market price for these credits fluctuated significantly, reducing the ability to predict future earnings, and therefore borrow against them. Moving to longer-term secure offtake agreements enabled Archaea to secure future revenues and borrow against them, in the form of green bonds to get the most attractive rates.

Case Study 2 - Community solar

As well as thinking about companies going from FOAK to NOAK, one can look at whole sectors making the transition too. One example is community solar. Despite the success of utility-scale solar in the mid-2010s, community residential solar presented considerable risks to investors due to its novelty as a business model, characterized by uncertain offtake agreements. Traditionally, onsite utility solar projects are sold to a single, creditworthy offtaker under a long-term contract. However, Generate Capital identified an emerging opportunity enhanced by regulatory incentives and adopted innovative financing structures and partnerships to pioneer community solar in Minnesota.

Thanks to David Yeh, Missa Sangimino-Ludwig, Natalie Volpe, Deanna Zhang, Chadd Garcia, Scott Jacobs, Jonah Goldman, and Peggy Flannery for their expert advice. And one more huge thanks to David Yeh for making it all the way to this fourth-of-a-kind feature with us.

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs

Get the data, insights, and case studies behind the next wave of climate tech

What we heard at the Davos of Distributed Energy Resources