🌏 Hot off the press: China’s 15th plan for the era of security

A breakdown of China’s new FYP and what it means for the next decade of the energy transition

Part IV: Demystifying tax equity investments and IRA’s clean tax credit bonanza

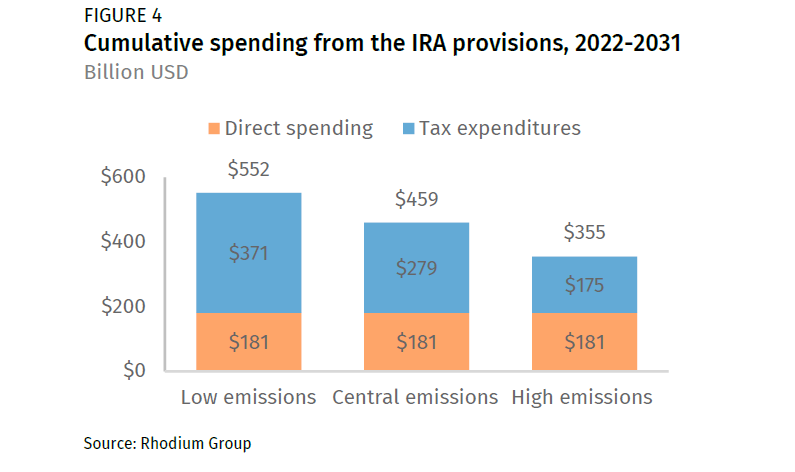

Taxes may make your eyes glaze over, but the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) promise of a whole pot of gold at the end of the green rainbow is reason enough not to sleep on tax credits. Of the much anticipated $1.7T (yes, with a T) public and private bonanza of IRA climate spend provisions, tax credits alone are predicted to make up over 2/3rds of all spending, essentially bequeathing much of the US’s decarbonization authority into the hands of—get this—the IRS.

Of course, this isn’t clean energy’s first tax credit rodeo. But new dramatically expanded IRA provisions and pending interpretation have carbon cowboys & cowgirls lining up to lasso profits from the promised spending stampede. The path to financing climate tech projects has changed course. Grab the reins and hop in the saddle, it’s time to giddyup and steer the ride down the new cost curve for clean energy. And yes, we’re still talking about taxes 😆

Tax equity financing is not new. In fact, ~40-60% of wind and solar projects costs in the US today are covered by tax equity investments. Parties that owe income tax have long managed their liabilities strategically, and the government has long leveraged tax savings to spur investment in strategic priority areas. Namely, the low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC), the new markets tax credit (NMTC), and energy-related tax credits like the renewable electricity production tax credit (PTC) and energy investment tax credit (ITC).

And these credits already have a track record of successfully supporting renewable energy growth. Since the tax incentive for solar energy was enacted in 2006, the US solar industry has grown more than 200x.

For those not (yet) fluent in the intricacies of tax law, there are a few key terms to understanding how tax credits fit into the larger capital stack for climate tech projects.

Developer equity: Developers contribute their own capital to cover a portion of the project costs.

Debt financing: Lenders provide borrowed, non-dilutive capital to fund the project.

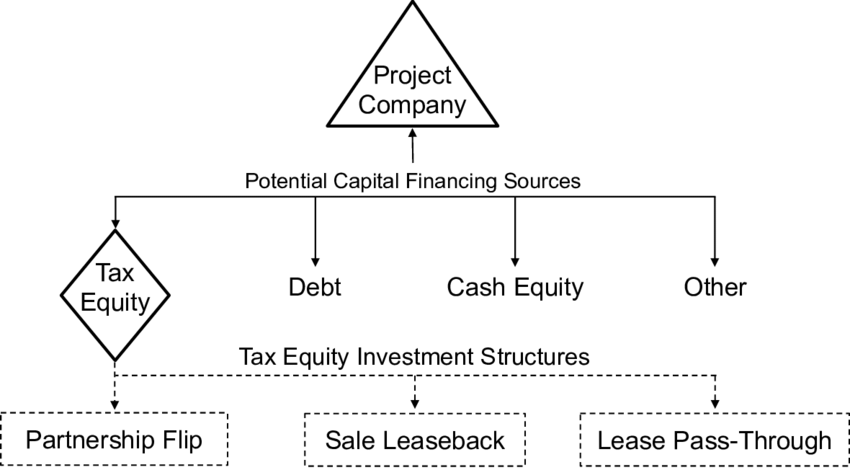

Tax equity: Governments offer incentives as tax credits which can be monetized as an offset to the taxpayer’s tax liability. If developers don’t have enough taxable income to take advantage of the tax credits, they can partner with a third-party tax equity investor (e.g., banks or large companies) that owes a significant amount in taxes and provides initial capital in return for claiming the credit on their tax liability and receiving a portion of the cash generated by the project. Prior to the IRA, the complicated partnership structure of tax equity was the only way for developers to monetize their tax credits, because the government historically wanted to ensure that anyone benefiting from the credits was an at-risk owner of the project.

Production tax credits (PTC): Revenue for investors earned as a per-kWh tax credit based on the production of energy generated and sold, paid over a 10-year period.

Pre-IRA example: A wind project qualified for a tax credit equal to 2.5 cents per kWh of energy produced.

Investment tax credits (ITC): Covers costs to get projects up and running by allowing taxpayers to deduct a percentage of the project’s total cost from their tax liability, provided as a one-time credit once operational.

Pre-IRA example: A solar project qualified for credits amounting to 26% of total costs.

Depreciation benefits: Investors receive a tax deduction each year for any normal wear-and-tear or decrease in the value of assets related to a project. Some renewable projects qualify for 100% depreciation the year they begin operating.

Recapture risk: There is a risk that the tax equity investor must repay a portion of the tax benefits if projects that elected ITCs are taken out of service or sold during the five-year recapture period.

Tax equity plays a key role in project financing by combining federal tax benefits with revenue generated by the project. Funding for a new solar energy project, for example, is not just money from developers and debt from lenders. Tax equity investors cover ~35% of typical solar project costs and ~65% of typical wind project costs in exchange for tax credit incentives, as well as cash returns once the project is generating and selling clean electrons.

Tax equity is considered a passive investment with a target internal rate of return (IRR) based on available federal tax benefits. After-tax returns to tax equity investors generally range from 5-12%.

Recurring tax equity investor characters are usually big organizations like insurance companies, banks, and mega corporations. Why? Because they have such large tax liabilities that juicy tax credits are worth the squeeze (i.e., the time and money spent to invest through tax equity deals). Other players include the lawyers, insurers, and accountants that execute these complex transactions.

1. Project development: The project developer identifies a solar project opportunity, performs feasibility studies, secures necessary permits, and develops the project.

2. Project financing: The developer or (more often) the sponsor of the projects seeks investors to finance it, including tax equity investors interested in shrinking their tax liability by investing in renewable energy projects.

3. Negotiation & structuring: The project developer and tax equity investor negotiate the terms of the transaction (e.g., allocation of tax benefits, financial returns, recapture provisions) and determine the structure of the transaction, such as partnership flip, inverted lease, or sale leaseback.

4. Financial due diligence: The tax equity investor conducts due diligence to evaluate the project's financial viability, reviewing financial projections, assessing the project's revenue streams, and analyzing the financial and tax implications before the parties execute the necessary legal agreements (e.g., partnership agreements, lease agreements, and financing documents).

5. Investment & tax benefit allocation: The tax equity investor provides funding to the project in exchange for an ownership interest, partnership interest, or ownership of the asset, depending on the chosen structure. The tax benefits, in this case as the ITC, are allocated to the tax equity investor as agreed upon in the negotiated terms.

6. Project operation & tax credit utilization: The developer continues to operate and maintain the solar project, ensuring its efficient performance and compliance with contractual obligations and regulatory requirements. Meanwhile, the tax equity investor utilizes the tax credits granted to the project to offset their tax liability, reducing their tax burden and receives financial returns from the solar project.

Partnership flip: A developer “flips” their partnership interest to the tax equity investor, allowing the investor to receive the majority of tax benefits while the developer retains residual ownership and operational control.

Inverted lease/Lease pass-through: A developer forms a partnership entity with the tax equity investor who contributes capital in exchange for a partnership interest and claims the tax benefits. The partnership then leases the asset back to the developer/owner who continues to operate and maintain the asset while paying lease payments to the partnership.

Sale-leasebacks: A developer sells the asset to a tax equity investor and immediately leases it back from the investor. The investor becomes the new owner of the asset and receives the tax benefits while the developer retains possession and use of the asset by paying lease payments to the investor.

Tax equity investors negotiate target investment terms by analyzing 1) potential tax benefits available to them and the time period through which they can accrue them, 2) the type of project or asset(s), including design and associated risks, and 3) other sources of financing being used for the project.

Historically, tax equity has been dominated by a few super-active players, due in large part to the complexity of the transactions. In 2022, tax equity accounted for ~$18B of financing for projects, yet >80% of the demand was concentrated in just 10 corporate tax investors. JP Morgan and Bank of America alone have made up more than half of those investments in recent years.

Of course, it’s not only big banks that stand to benefit from tax liability write-offs. Some nifty new IRA provisions (much more below) significantly boost supply of tax credits and broaden the pool of potential investors, spurring demand, and funneling new capital into a wider range of climate tech projects.

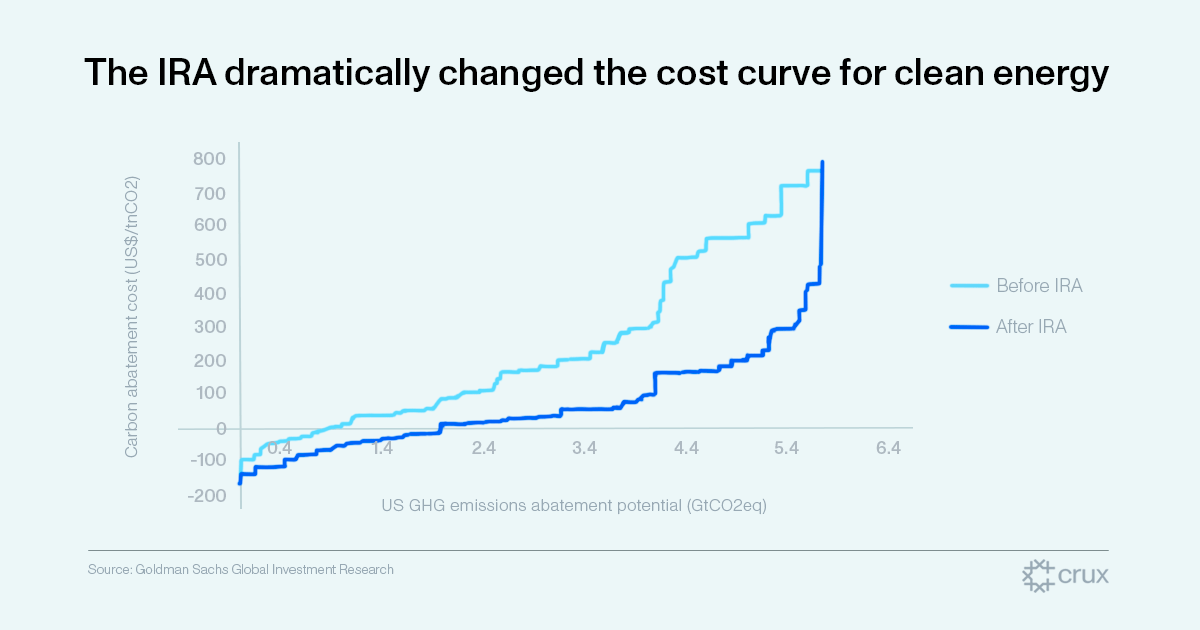

The IRA accelerates everything. Our analysis estimates a 40% cost decrease on average for climate technologies and our IRA tracker breaks out the individual credits for each type of tech. Norton Rose Fulbright lawyers outlined a similarly exhaustive and helpful ITC and PTC cheat sheet.

Throughout the multi-line madness, IRA aims to achieve a majority of its decarbonized savings through tax credits, which could drive ~$83B in tax attribute transactions per year by 2031, per Credit Suisse estimates, and ~$370B of new energy-related tax credits over the next 10 years, per PwC.

Along with brand-new credits, a significant portion of that massive IRA tax spend is made possible by extending and expanding existing clean energy tax credits. The bill stretches current federal solar and wind incentives through the end of 2024 and then creates a “tech neutral” tax credit approach through 2032.

These IRA tax credits have two tiers: the base rate and the bonus rate. This second tier is a game-changer since it’s 5X the base amount (!) for projects that meet prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements. The IRA also includes additional incentives (or “adders”) that provide tax credits to projects meeting certain critical supply chain or geographic criteria, like supporting advanced manufacturing job creation in communities that have historically relied on fossil fuels.

The cherry on top? Adders are stackable too. These additional credits can stack on top of ITCs and PTCs, potentially utilizing tax benefits to finance more than half of project costs. The total value of tax credits a project is eligible for can increase substantially if they also qualify for add-on tax credits for:

Labor practices

Energy communities

Domestic content

Environmental justice

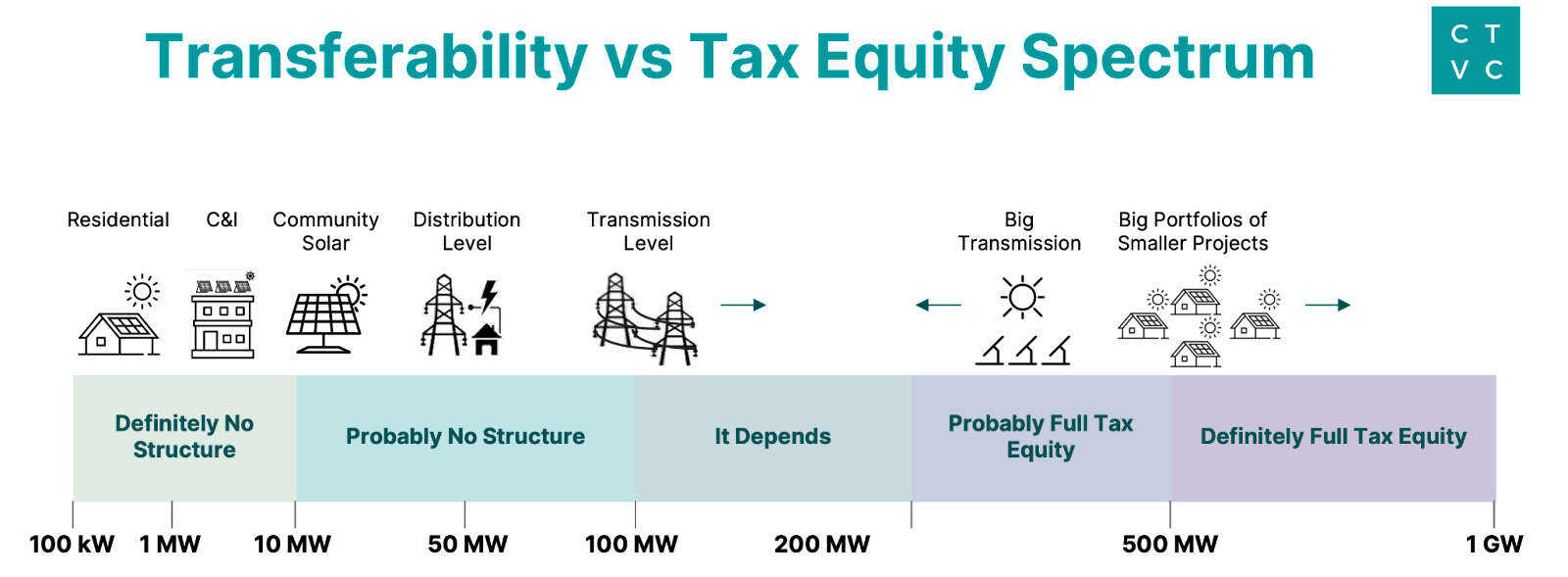

In the past, these federal tax credits were “non-transferable,” which meant only the owner of the project or asset was able to claim them. This necessitated the creation of complicated structures for tax equity deals that give investors the opportunity to utilize the tax benefits. Given its complexity, tax equity has principally been the domain of banks and insurance companies that have the resources to pay experts to put these deals together.

Many more businesses could be making use of tax credit strategies, but most don’t, due to the high costs and financial sophistication of tax equity investing today. That lack of participation has left more than $400B in underutilized tax liability on the table—and many unconstructed clean energy projects on the drawing board.

Now, the IRA introduces a new transferability mechanism (familiar already to states offering low-income housing credits, alternative energy credits, etc.) that enables nine types of federal clean energy tax credits to be sold to unrelated third parties through a one-time purchase. The ability to buy tax credits following the IRA makes it much easier to get access to the credits.

Demand, meet supply. The small pool of existing tax equity investors will not be able to absorb the swell of new tax value created through the IRA. Transferability opens up this greenfield supply to new buyers of tax liability write-offs—a substantial jump in demand considering US corporations paid $334B in 2022 taxes. If estimates hold true and corporations monetize $83B per year of IRA-incented tax credits, that would mean ~16% of all 2031 corporate tax liabilities get allocated to tax credits.

While tax equity will continue to be used widely, simplifying the process makes it possible for smaller investors and developers to participate. With decreased risk, it also allows investors to potentially branch into projects with less mature or unproven tech, potentially helping to fill gaps in financing.

Transferability aims to make tax credit transactions accessible to a larger number of investors by making them less complex and less costly, but traditional tax equity structures aren’t going anywhere. They still have a few advantages over transfer credits for certain investors and projects.

The cost-benefit equation weighs the importance of an investor’s ability to monetize step-up and depreciation through more expensive traditional tax equity transactions against the lower-cost option of transferable credits that don’t currently capture the fair market value step-up (which can increase the overall tax credit amount) or asset depreciation.

The reality is that this choice is not always an either/or. It’s likely that tax equity and transferability will be used together with in a hybrid structure, where tax equity partnerships monetize depreciation and realize the true fair market value of the project, then transfer the tax credits… the machinations of which would require another 15 pages to detail.

Investors: For the big tax equity investors, like large banks, the ability to monetize depreciation and step-up value—which goes away when selling transferable credits without a partnership in place—is often worth the cost of lawyers and other experts to conduct diligence and write contracts that mitigate the extra risk.

Projects: Tax equity investments will likely still be the norm for large-scale solar, which is a plus for the developers or sponsors of those solar projects, who also want the amount they’re paid for tax benefits to include depreciation.

Investors: For investors that don’t want to engage in the complexity of tax equity structures or don’t have the resources to hire a team to execute on them, transferable credits are likely to win out due to the lower transaction costs. A one-time purchase of a tax credit, rather than buying credits and investing in the project, also makes transferability simpler and less risky. This allows corporations without experience in tax equity investing—to buy a lower-risk credit when it’s generated by the project, instead of taking on the risk of losses upfront by funding prior to the project completion, a requirement in tax equity.

Projects: Traditional tax equity investing has worked well for residential solar and utility-scale projects, but transferability will help cover the “missing middle”—projects like commercial and industrial (C&I) or community solar. Additionally, transferable credits will be a boon for projects that didn’t previously qualify for tax equity investments, such as standalone energy storage, and could facilitate lower-risk investments in emerging tech that may not yet be suitable for underwriting with tax equity structures. Developers also benefit by gaining the ability to split up tax credits from a single project and sell them to multiple investors.

The refundability or direct pay mechanism in the IRA gives some developers the option to sell their tax credits and receive a cash payment from the US Treasury. That means tax equity investors are not involved and developers don’t have to give up a piece of the tax benefit value in these transactions. This change is relatively narrow, applying only to specific types of projects and organizations, including:

Leaders from more nascent climate tech sectors like CCUS and hydrogen advocated to include direct pay in the IRA, since tax equity investors have low risk appetites.

The market will need to absorb more participants, more deals, and more dollars, leading to a significant increase in fragmentation and the entrance of many new buyers.

Scaling the market and coordinating that dramatically larger pool of projects, divisible credits, and buyers will take a coordinated response from the private sector to realize the goals of the public sector.

The government has created a massive new asset class around transferable tax credits. Banks, large tax advisors, and existing syndicators are all taking an active role in the formation of this new market, as well as a number of other new startup entrants.

One new company answering the clarion call is Crux Climate, which announced a $4.6M fundraise led by Lowercarbon Capital in April. Crux has assembled a multidisciplinary team from across the highest levels of the Treasury Department, energy industry, tax equity, financial services, and software to build an ecosystem for developers, tax credit buyers, and financial institutions to transact and manage transferable tax credits.

"New markets evolve to become more standardized, efficient, liquid, broad-based, and transparent, but typically require new solutions to achieve that," Crux CEO Alfred Johnson said. "Players like financial institutions are going to play a critical role anchoring this new market and need the tools to scale the syndication of tax credits. Similarly, developers, buyers and other parties in the transactions will benefit from tools to connect with each other and streamline transactions."

Innovators: Atheva, Basis, Crux, Evergrow, Ever.green, Reunion Infrastructure

While we can draw comparisons to LIHTC or solar PTCs, no one can say for sure what this new tax credit marketplace will look like in practice just yet.

These transactions are complicated and have traditionally required more intense due diligence before tax investors are willing to enter into partnerships with project developers. Plus, there’s still a lot TBD about these credits—and transferability in particular—that the IRS will have to address before there’s a clear picture of how this market will work.

This support for clean energy financing has to be deployed through the tax code, and that creates its own challenges for the IRS, which will need additional resources to effectively roll out the clean energy incentives. The IRS was supposed to get an $80B infusion through 2031 to improve operations, update tech, and hire more staff. But Republicans rescinded $1.4B of that funding in the debt ceiling legislation and are aiming to knock another $20B off the remaining total, potentially causing everything at the IRS—including credits for clean energy deployment—to move more slowly.

Enabling project developers to sell tax credits provides much-needed capital for deploying climate tech, but what happens if the tax benefit is allocated to a third party and then the developer fails to meet the tax credit requirements and there is a recapture or disallowance of the tax credits (e.g., the credits were improperly valued)?

To keep the government from knocking on the investor’s door to recover the value of the credit if the credit is misvalued, taken out of service, or the underlying project is sold during the recapture period, developers and investors have to manage recapture risk. Whether the buyer or the seller carries recapture risk is one of the most crucial open issues the IRS has yet to clarify. In order to incentivize developers to protect against this risk, the forthcoming rules may end leaving multiple parties exposed to recapture risk.

Today, tax equity transactions for solar often include buyer-friendly recapture or indemnity provisions where the developer agrees to repay part or all of the tax benefits to the tax equity investor if a project fails or tax laws change within a certain period. Tax equity insurers could also step in to handle this recapture risk and some are already writing insurance policies on transferability.

For transferable credits, the IRS still needs to issue further guidance on who is ultimately responsible for recapture risk. The way these rules are written will influence the pricing of tax credits, as buyers will want to pay less for the credits if they’re taking on more of the risk. In March, Lily Batchelder, Treasury Department Assistant Secretary for Tax Policy, gave a speech indicating that transferability guidance would be out in Q2, so expect updates any day now 👀

More guidance is also needed on:

What the development of a transferable credit market looks like will depend most on this future IRS guidance. While a nascent market is beginning to emerge, it could take years before a true market develops.

A huge thank you to Simran Suri, Elle Brunsdale, James Prussing, Allen Kramer, and Alfred Johnson who provided crucial insights on the complex world of tax equity.

ICYMI, this is the fourth installment in our series on climate tech project development. Check out our other deeps dives:

Questions or comments about what we covered or what we missed in this post? Reach out at [email protected]

A breakdown of China’s new FYP and what it means for the next decade of the energy transition

We asked, you answered, and experts weighed in on 2026

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs