🌎 Q1 2025 roundup: top deals, exits, and new funds

Investors hope to set off a chain reaction with new nuclear funding

A Q&A with Precursor's David Yeh and Mark1's Julian Ryba-White, new strategic partners in the ecosystem

After four years of historic public investment in clean energy, the future of first-of-a-kind (FOAK) climate projects now hangs in the balance. Under the Biden administration, billions in DOE loan guarantees and tax credits kept projects once deemed too risky for private capital on track. But as political currents shift, the tightrope ahead seems a little less stable.

With policy and fiscal volatility on the horizon, government-backed funding — once a crucial de-risking tool — now comes with delays, legal battles, and the looming risk of clawbacks. Venture and private investors, who saw federal incentives as a green light for deploying capital, are recalibrating. The question isn’t just whether FOAK will survive — it’s how.

As the cohort of startups undertaking their FOAKs grows, so too is the ecosystem around them. A new class of strategic players has emerged around FOAK in recent years: Enter FOAK advisors and service providers, key new partners in the ecosystem.

In this newsletter, we break down the key players shaping the FOAK ecosystem, the pressures they face in 2025’s uncertain investment climate, and a Q&A with the builders themselves — David Yeh, partner and founder at Precursor, and Julian Ryba-White, CEO of Mark1. Both are working to de-risk FOAK projects and help climate startups bridge the gap between innovation and execution.

With CapEx challenges and federal funding uncertainties, investors in first-of-a-kind (FOAK) projects are adapting at different speeds. Government agencies like DOE’s Loan Programs Office (LPO), ARPA-E, and the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED) have played a key role in de-risking early-stage climate projects through grants, loans, and tax credits. However, shifting priorities may slow future deals.

Outside the US, public funding remains more stable. The European Union has recently committed billions to industrial decarbonization, Canada’s Clean Growth Hub supports climate tech innovation, and Asia-Pacific markets are aggressively backing clean hydrogen, ammonia, and advanced nuclear through public-private partnerships.

Catalytic capital providers, including Prime Coalition and Builders Vision, specialize in patient capital, filling funding gaps where venture capital pulls back. Meanwhile, private investors remain selective. Climate VC and infrastructure firms like Lowercarbon Capital, TPG Rise, and Decarbonization Partners continue backing proven technologies, while infrastructure giants like Brookfield and Macquarie place big bets on megaprojects. Without government support, debt financing could become more expensive, pushing investors toward alternative funding models.

FOAK projects often stumble in execution due to challenges in technology validation, supply chains, and deployment. Engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) firms like Bechtel and Fluor bring crucial expertise to companies lacking in-house capabilities. While technology suppliers vary by industry, supply chain bottlenecks and tariffs remain hurdles. Once operational, FOAK projects demand deep expertise — some, like LanzaJet (sustainable aviation fuel) and Fervo Energy (geothermal), manage their own facilities, while others outsource operations and maintenance.

Long-term viability also depends on stable revenue. Corporate offtakers and supply chain partners are securing demand through long-term agreements, while energy incumbents invest strategically to support scaling. Meanwhile, community and policy advocates help align FOAKs with local priorities and workforce needs — critical amid policy uncertainty.

To navigate these increasingly complicated ecosystems, insurers and advisory services are playing a larger role in securing FOAK projects. Risk-transfer providers like New Energy Risk help de-risk early-stage projects by offering performance guarantees and insurance solutions, enabling FOAKs to secure lower-cost debt. Alongside, a new class of advisory firms, such as Mark1 and Precursor, led by FOAK veterans, offer financial, legal, policy, and project development support, particularly as government backing becomes less predictable.

To dive deeper into the evolving FOAK landscape, we sat down with two leaders shaping the ecosystem: Julian Ryba-White, Co-Founder and CEO of Mark1, and David Yeh, Partner and Founder at Precursor.

Julian, leading a team with extensive project development experience and supported by RMI, Third Derivative, and Deep Science Ventures, was formerly a Principal at Nokomis Energy, Senior Director at TenK Solar, and Manager at SolarCity, now leads Mark1 — a Developer-as-a-Service firm for specializing in project execution for industrial climate tech FOAKs.

David, a veteran climate investor with over 20 years in infrastructure and venture capital, including in roles at the Obama White House, Generation Investment Management, and the World Bank. With the newly launched Precursor, he aims to offer a FOAK project development and advisory platform for gigaton-scale climate solutions.

Here’s what they had to say about the state of FOAK financing, execution challenges, and advice for innovators getting these critical projects off the ground.

CTVC: Financing is notoriously a major problem for FOAK projects. Why is that?

Julian Ryba-White: FOAK projects require significant capital investment, but they don’t fit neatly into venture capital or traditional project finance. Venture capital is designed for fast-scaling software and hardware—not large-scale infrastructure. Venture capital returns that can adhere to the power-law don’t come from investing in capital expenditures, even if venture funds had that kind of AUM (and, of course, most don’t). Meanwhile, project financiers won’t touch FOAK because of unproven technology and execution risk. Why would they against the opportunity cost of more stable, predictably cash flowing projects when the constituents they’re trying to serve are pensions and insurance pools?

Historically, industrial technologies scaled over 100 years, reinvesting profits from one plant into the next. We don’t have that kind of time to reach net-zero goals, and technologies are more rapidly scaling down the cost curve. Just look at solar panels and batteries and semiconductors. The pace of innovation has changed, so should the iteration of infrastructure. How do you accelerate development instead of just waiting for one plant to generate enough profit to build the next? We see this as an immense opportunity, driving more opportunities to a large and growing private credit segment.

FOAK certainly has a financing problem, but it’s not just that—it’s also a talent and capacity problem. These novel climate tech teams are rarely prepared to successfully navigate all stages of commercial-scale infrastructure development. Even the best developers with flawless execution will struggle with FOAK because it’s never been done before.

We like to say, technology developers aren’t project developers, and project developers aren’t technology developers. Yet, we often expect one to turn into the other, and they could use help doing that.

David Yeh: Finance is becoming particularly important right now because the missing piece of capital in the U.S. has been the Department of Energy’s (DOE) Loan Programs Office (LPO) and the Office of Clean Energy Demonstrations (OCED). And there’s a big question mark on what they’ll look like in six months.

Another critical aspect of project development is having a strong understanding of infrastructure-based business models. At Precursor, we see many companies that don’t just need help at the FOAK or pilot stage. They need support right now, at Seed and Series A, when they’re figuring out their long-term business model. Are they an OEM, a developer, or a licensor?

Many startups are, in fact, launching three companies in one without realizing it. And most of them will need to become their own project developers—at least for their first one, two, or three projects. This is not something you can outsource.

Many startup founders are fresh from their PhD programs. They have the vision and the ability to bring new technology to life, but that technology won’t scale without a strong commercial and financial foundation. It’s like a three-legged stool: technology, commercial strategy, and financial strategy. If you’re missing one, you’re in trouble.

CTVC: How do your organizations help startups overcome these challenges?

Julian Ryba-White: Our focus is on planning and execution for the first commercial project with a goal of getting to FEED within 18 months. We do this by partnering with high performing teams, defining their project development plan including sourcing feedback from an agreed-upon ecosystem of offtakers, financiers, EPCs, insurers, law firms and other experienced FOAK solution providers.

We then propose a specific structure through which Mark1 can directly support boots on the ground development along with providing development capital to support the work. Our goal is to integrate into the startups team, providing additional resources with specific expertise in project development to enhance the startup’s efforts.

Part of what catalytic capital is asking is: Where can we lean in a bit more and start pulling these technologies forward? We do this by providing strong technical assistance and contracted, hands-on involvement with the project development and commercialization lens.

There’s no one size fits all here. That’s why our process is bespoke — fit for purpose for each company. It’s programmatic in the sense of bringing good, structured project development methodologies, but each project is unique. In practice there are two major engagement phases:

1: Planning phase – Helping startups map risks, develop commercialization strategies, and prepare for project finance, for up to six months, depending on the existing state and maturity of the project. It’s like measuring twice, cutting once. We’ve got to allow ourselves and the founders time to really make sure we’re on the same page about what makes sense and what the risk profile looks like. In a sense, it’s about helping them understand diligence and how to think like project developers. We like to say that – unlike your project financier – we’re not doing diligence “on” you, we’re doing diligence “with” you. We also need to get to know each other and give them tangible, strategic work like development plans, schedules and budgets that will actually drive value for their next steps.

2: Co-development phase – Structuring joint development agreements to align incentives and share execution risks. This is where we have put pen to paper on how we can work together as a joint venture, and Mark1 starts to drive execution. For the right projects and teams, we move into co-development. This includes delivering on workstreams and milestones; hiring and managing third-parties; maturing capital relationships and lastly, serving as advisors to the collaboratively-defined services, deliverables, and compensation structures that are aligned with project success determined in our Planning phase. We act like the project management conductor and help every party play the correct part of the symphony, even when we occasionally pick up a violin or a guitar where needed. (Please do not expect literal music performances from Mark1 staff.)

Across these two phases, we shape ourselves to the existing team of the project – talent that’s inherently changing over the life of the project. That’s what enables us to work collaboratively with experts and friends like David.

David Yeh: At Precursor, we guide startups through the entire FOAK lifecycle—from business planning to demo pilots, FOAK deployment, and mass scaling.

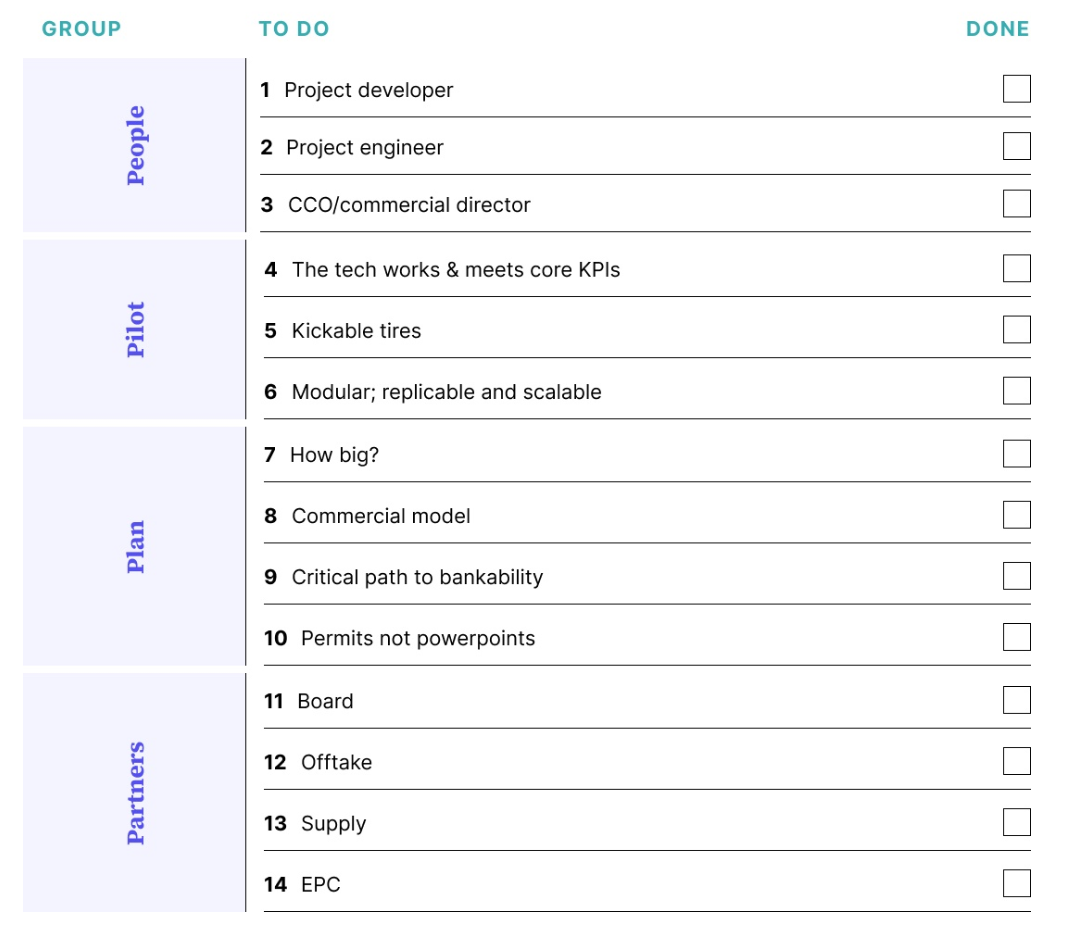

We take an embedded approach, acting as the startup’s “Chief FOAK Officer” to help with:

But we don’t just consult—we teach startups how to do this themselves. FOAK is a 5–10-year journey, and companies need to build internal capabilities so they’re not reliant on advisors forever.

CTVC: What are the most common mistakes startups make in FOAK execution?

Julian Ryba-White: Finding the right partners and creating the right relationships. FOAK is not transactional. It requires that everyone understands the project, what works for each-other and what doesn't.

You have to understand those things early so that when the plan changes — and it will change — you can go back to everyone and keep the train on the tracks.

When we were designing Mark1, we talked to hundreds of companies that have gone through commercialization and heard a consistent theme: project development — specifically across technical, commercial, financial, siting and regulatory disciplines — was much more complicated than they expected. That’s why building the project development layer is at the core of our focus. The best project development processes establish a plan, establish capital controls, and then, most importantly, a method for rapidly iterating that plan and keeping everyone on the same page.

When you’re developing a project, there’s also a timing issue around creating visibility and getting feedback — if I bake things too early on for my offtake, I might be waiting for pilot data or financing, and suddenly that offtake contract starts to go stale because I waited too long.

Timing is crucial, but you can’t always control it. You have to go into this with eyes wide open to the reality that timing risk is part of FOAK development, and engaging the right partners and the right time is part of the art.

David Yeh: Project development isn’t something you can outsource. It’s like outsourcing the care of your newborn. Most startups don’t have design lock when they’re doing demos, pilots, or FOAKs. They can’t just throw it over the wall and tell a developer, “Go do this.”

What I’m seeing more and more is companies trying to outsource this responsibility, using what I call a “hold my beer” strategy — where they assume, “Oh, the EPC (Engineering, Procurement, and Construction firm) will just handle it.” EPCs are great, but they are not developers. They’re partners in engineering and construction.

CTVC: How do you structure your organizations’ financing to align with long-term project success?

Julian Ryba-White: Mark 1 is structured as a Public Benefit Corporation (PBC) backed by philanthropy and corporate sponsors like RMI and DSV.

We use a two-phase model:

This way, we only succeed when our projects and founders succeed. We’re not just development capital, we’re embedded members of the co-developer team.

David Yeh: At Precursor, we focus on execution and mentorship. Our model includes:

But we don’t just consult — we teach startups how to do this themselves. FOAK is a 5–10-year journey, and companies need to build internal capabilities so they’re not reliant on advisors forever.

CTVC: Final thoughts for climate startups tackling FOAK?

Julian Ryba-White: Your commercialization strategy is crucial, spend the time to understand your business model today, how it might evolve alongside your first, second and nth projects. What are you selling and where does that fit in the full value chain? Who are your real partners, the ones that really care about success both within and beyond project number one?

Those first decisions are incredibly important. Even when you get them right, you’ll probably need a blended capital stack to get your first project done. That’s okay, but make no mistake that every part of the capital stack needs to believe you’ll do five or ten more projects.

David Yeh: Don’t rush FOAK. The missing middle is expertise. Expertise derisks projects and makes them bankable. The capital will then follow. Take the time to:

Precursor is looking to partner with the next generation of energy and industrial innovators. For more information, visit Precursor.earth.

Applications to work with Mark1 are now open. Get more information on working with Mark1 on its website and apply here.

Investors hope to set off a chain reaction with new nuclear funding

What’s actually working while the rest of the climate capital stack stutters

Announcing Sightline Climate's $5.5M Seed fundraise from Westly and Molten