🌎 Two climate investors on raising in today's tough market

Q&As with Sophie Purdom, who just closed first-time Planeteer Fund I, and John Tough, who recently closed Energize Capital's mega-fund Ventures Fund III

Electrifying ground transport is well underway, but taking to the skies without fossil fuels is a challenge on a different plane.

We spoke with co-founder and CEO Andrew Symes about the company’s recent $23M fundraise, business model, and strategy for scaling SAFs.

Tell us a bit about your background. How did your experience at BP and as an investor lead you to co-found OXCCU?

I studied chemistry at Oxford, so I've always loved chemistry. Then I left, because I didn't want to do a PhD. I ended up joining BP on the commodity trading team, and got to see how the whole energy system works. It helps now to know what we're up against, in terms of what we have to replace. But ultimately, my mind was always going back to technology and the world of science and innovation. I left trading to work for BP Ventures, investing in startups on behalf of BP. I left to join IP Group, a financial VC which specializes in deeptech university spin-outs—in the UK, mainly—and I fell in love with OXCCU. I met Jane Jin while she was working for the Oxford Patent Office. Then we met Tiancun Xiao, and decided that his work was the most exciting thing we've seen. We both quit our jobs to run it—myself as the CEO and Jane as COO.

Where do things stand when it comes to decarbonizing aviation? Will the future be electrification or SAFs?

I think most people at least agree that for long-haul flights we still need hydrocarbons. And people still are very keen to fly. People have family and friends in different countries and continents, and it's the way that people get around. People want to carry on with that, but they want to remove the climate guilt that they have around the emissions. That's the challenge for everyone: How do we make hydrocarbons so people can keep flying, but without the climate impact?

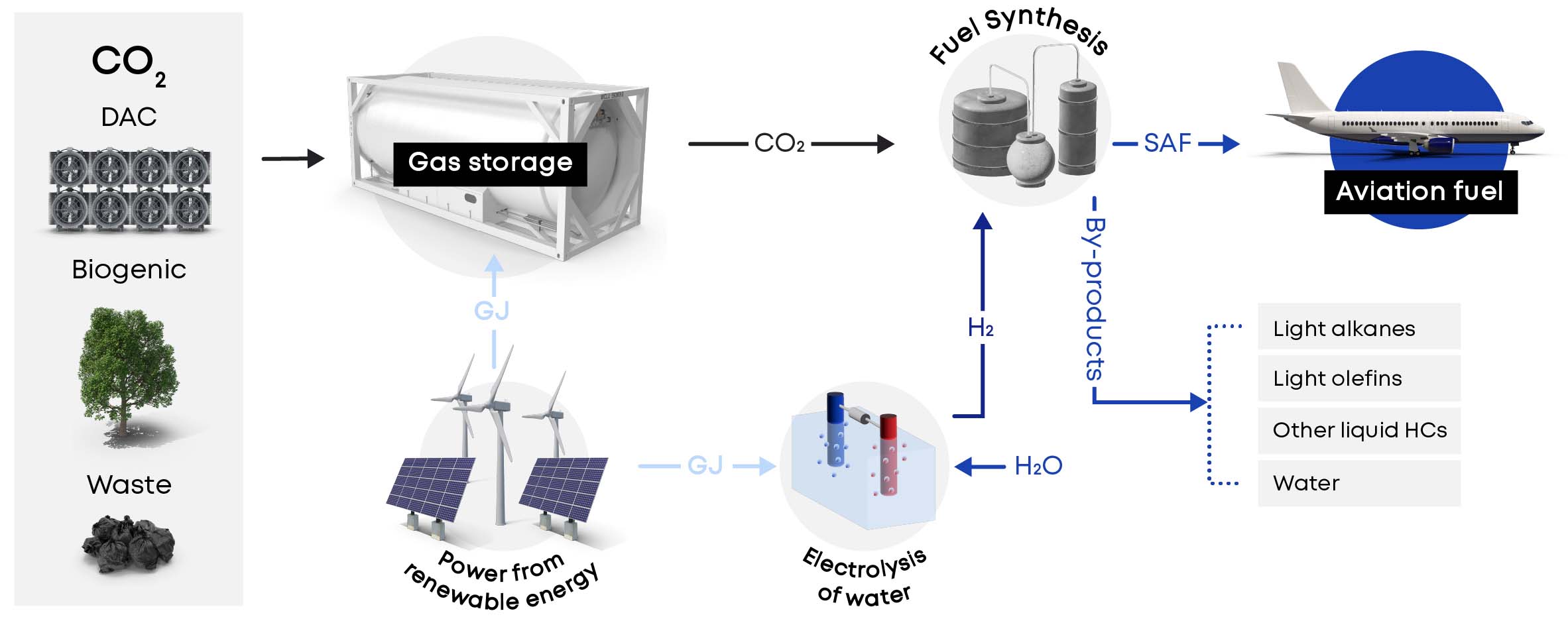

The first attempt was the first-generation biofuel, the vegetable-oil based fuel. And what's very different now, compared to the early 2000s, is that no one wants to expand that to cover the whole industry because of land use impacts and competition with food. That's really why there's this increased interest now in using CO2 and combining that with hydrogen to make sustainable aviation fuel. This is the next logical step, and the challenge to date has been cost. We're helping get that cost down significantly, because we've got a process that's one step rather than two.

Describe OXCCU’s technology. What differentiates it from other SAF solutions?

Our innovation helps solve the cost issue. We're simplifying a two-step process—most people are doing what we're doing in two steps—into one step. It does that through a breakthrough in catalysis that enables both reactions to happen on the same catalyst surface. So essentially, you get a simplified process, which means a reduction in CapEx to build a plant and a reduction in OpEx, because you've got less byproduct (you're making less of the things that you don't want). You have less inputs in terms of heat and hydrogen especially, which is the most valuable bit. More of that goes into the products that you want.

OXCCU is also developing tech for chemicals and biodegradable plastic products. Are those processes complementary to producing SAFs? Or separate?

Completely different catalysts. Where we see ourselves is as a CO2 catalysis company and reactor design company, rather than the product developer. So we plan to have a range of disparate CO2 catalysts that can make different products—whether you want aviation fuel-like components or you want syngas or methanol or plastics. We plan to have a range of different catalysts that can do that. But there's different catalysts that make the PGA plastics. It's a very different process to the process that makes the jet fuel components.

We're really focusing on the catalysis parts. Rather than being focused on selling the fuel, per se, we plan to license our catalysts and reactor designs. Of course, we need to build plants before people buy them, but the reality is, we will move to a licensing model—similar to companies like Johnson Matthey or Topsoe or UOP Honeywell today. Those types of companies sell to the existing refining industry. They have a range of different catalysts that could do a range of different things to make a range of different end products, rather than being the refiner.

What are the plans for this funding and what do you expect the commercialization timeline to look like?

The reason we raised the money was to build a plant in Oxford Airport—that will be our first demo plant. And we’re expanding the team as well. Then we’ll have to build one more larger plant before we move to commercial scale. We will have to fund these two plants ourselves, mainly, rather than people being willing to buy them. In terms of timeline, we’ll build them over the next three years—hopefully two, but more than likely three—and then we'll be in a position to move to licensing. Ultimately, this industry just needs to see that the catalyst works at a reasonable scale for a decent amount of time. That’s the main priority, and that's what the industry players need to see in order for them to be able to make the decision to license.

Are there specific reasons you decided to stay in the UK?

The next two plants will likely be in the UK—certainly the Oxford airport one and the next one after that will be in the UK as well, just because that's where our engineering team is. And we need to be close to it to understand it. When we move to licensing, the good thing about that model is you can look globally. The three most attractive areas are the Middle East, Europe and the US, and we've got investors from all those regions. So we will be looking globally once we’ve done these two plants, but you want to be close to these first ones.

Why opt for licensing as a business model rather than production?

That's what we're really good at and That's what we have expertise in. We’ve spent a long time focused on catalysts and reactors. Lots of others will be really good at the product development side.

Where does the CO2 come from and how are you thinking about that feedstock as you scale?

The CO2 source is a big, hot topic—and quite a complex one. Essentially, for the demo plant, we can do tank [meaning we buy CO2 from the merchant market] and fossil CO2 [captured at the source of fossil fuel industry activities] to prove it works. But when you get to larger plants, you want to use a carbon source that produces a product with a good life-cycle emissions assessment. So for our larger plant, we’ll probably use biogenic CO2 [which is a byproduct of the biomass decomposition process]. Longer term, we can really use any CO2 source, but if you want a really good life-cycle analysis, then you do want direct air capture or biogenic CO2. But there's a huge opportunity to use fossil CO2 as well, if regulations allow and you aren't as concerned about your lifecycle analysis. So when we come to licensing, we'll be working with a lot of different CO2 sources.

What do you anticipate offtake to look like and do you expect a green premium on these products?

There's more work to be done before you end up at that final price and final green premium. But the reality is we've got a lot of people who want to take the fuel, want to work with it, want to blend it, want to see what they would do with it, and it is going to be a high value product. But we can't say right now what that price would be. We just know we've got a lot of people who are interested in getting hold of some of it, testing it, putting it into an engine, for example, burning it with other fossil fuel and seeing how it burns. Lots of work to be done by the existing industry. We aren’t looking to bypass that industry. We just want to work with it, because they are good at blending.

Who are your target customers?

Our customers are ultimately anyone who's got aspirations to do e-hydrocarbon projects. We need to persuade them that we've got the best catalysts and the best reactor to convert the CO2 and hydrogen that they’ve got into the products that they want. This includes the oil companies, obviously—we’ve even got Eni and Aramco invested. But also there are smaller ones. In Europe they've got companies like Sky Energy, Neste, and others who are really keen to try and do these projects.

What sort of adjustments are needed to blend or swap your fuel in for traditional jet fuel?

It should actually burn, hopefully, with less contrails. But currently, the Jet A-1 spec [the international standard for commercial jet fuel] requires things like aromatics, so people are going to have to blend until that changes. That will probably change in time, but it's a conservative industry. They're not going to change the specification quickly. Most people will be blending, but blending is not an issue, because we're not producing huge amounts of SAFs at the moment. We can just scale up over time, and I think the regulators are looking to scale it up over time, from small percentages today all the way up to much larger ones in the future. Simultaneously, people are looking at 100% e-SAF flights, which is helpful as well, because that gives people even more confidence that blending small amounts of it is absolutely fine. So lots of work is being done in this area by the existing industry.

What are the other challenges to scaling this type of SAF?

The main challenge is currently around costs. And hopefully that's where we come in and help solve that with a more efficient process that reduces the CapEx and OpEx of the plant. The modeling we've done has shown a 50% reduction in CapEx and a significant reduction in OpEx as well, because of less byproducts and better heat management.

Producing SAFs is an electricity-driven process. How are you thinking about sourcing that power?

It’s another factor that will impact your life-cycle analysis. So on one end of the scale, if you've got your own solar and wind, and you're only using that to make your green hydrogen, your life-cycle analysis will be better than if you pull it from the grid and the grid’s got some fossil sources in it. So it depends on how fierce you want to be with that and how few grams of CO2 per liter of fuel you want. But ultimately, you need green, or green-ish, hydrogen. It needs to be pretty green, otherwise it’s not worth doing. It’s another problem to solve, but it can be solved and I think it will be solved over time. Ultimately, it'll be the project developer that pulls it all together. They will arrange the offtake, they will buy the electrolyzer, they'll buy CO2 capture. And then essentially, they will look to buy a reactor and catalysts to convert the CO2 into hydrogen and that's where we want to persuade them that one step, rather than two, is the way to go. So in some ways, you don't need to solve all these questions. Different regions will have different criteria for what's allowed and different regulatory regimes to incentivize it— the [Inflation Reduction Act] or the ReFuel EU and all the other things that will be available.

What was it like raising this round? What made these investors a good fit for OXCCU?

For this sector, there's a huge amount of interest at the moment, to be honest. I know the sector as a whole is having challenges, but there is a lot of interest in SAF. Certainly we saw that with incredible interest from some really strong partners. And all of those companies whose names you'll see have got a very long track record, and a lot of experience, in investing. They will bring a lot of different skills and expertise to us. You can see the full value chain—starting from the renewable developer all the way through to the oil companies, energy companies and the trader, Trafigura, and then United Airlines as the offtaker.

Do chemical reactions catalyze your interest? Reach out! OXCCU is looking to add chemists and chemical engineers to their growing team.

Q&As with Sophie Purdom, who just closed first-time Planeteer Fund I, and John Tough, who recently closed Energize Capital's mega-fund Ventures Fund III

A Q&A with Precursor's David Yeh and Mark1's Julian Ryba-White, new strategic partners in the ecosystem

A Q&A with the DOE LPO director Jigar Shah and Solugen CEO Gaurab Chakrabarti