🌏 A tour of China's electrostate

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs

Part III: From numbers on a page to boots on the ground, there are plenty of challenges to bringing a project to fruition

Even when all the money is finally lined up to actually start construction on emerging climate tech infrastructure projects, moving fast and breaking things in the pursuit of hypergrowth does not work when scaling hardtech. The quickest path to climate tech project deployment is to measure twice and cut once, since there’s no quick code-fixing grace to be given in the land of physical assets.

Last week, we dove deep on project finance funding hurdles to deployment. This week, we’re back to dig into the practical operational strategies and human capital needed to get actual steel in the actual ground.

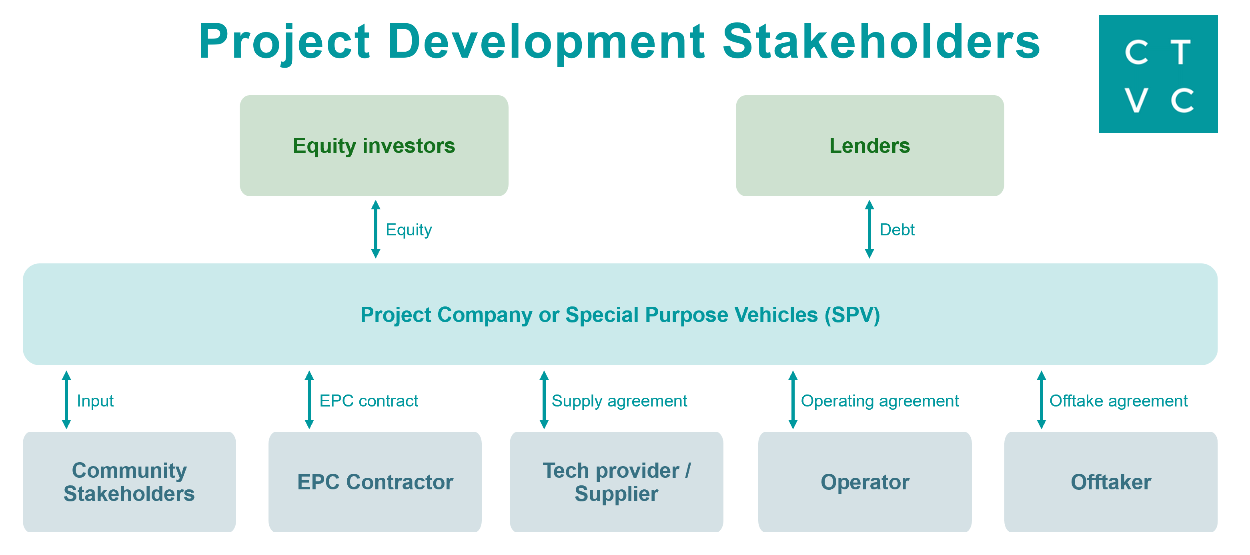

In Part I of CTVC's climate tech project deployment series, we deconstructed the bridge to bankability for financing first-of-a-kind (FOAK) or early commercial climate tech projects. But investors alone certainly don’t scale a project—engineers, builders, and developers do. Once financing is locked and loaded, it's time to then lock arms with an army of project stakeholders involved in getting a project over the line.

The question of who will pay for FOAK project deployments ties directly to how funding requirements align with project size scale-up. 'Go big or go home' doesn’t sit well within the project development playbook. Building too big and being wrong is a very expensive mistake. As a general rule, scaling a novel technology’s output beyond a 10x step-up can lead to untenable levels of risk.

“Investors are really going to want to understand what your plan is, and make sure you've got a smart plan to go about scaling, before they place their bet on you,” Kim Lovan, Associate VP of industrial manufacturing at Black & Veach, told us. “You don't just 200,000x everything and expect it to work.”

A few mitigating factors to consider in the path to scale-up:

But even with the savviest scaling plan, it’s nearly impossible to predict and then translate that estimate into exact dollars and cents. And the downside is steep. Selling valuable company equity to fund a project with VC dollars only to come up short is a potentially existential miscalculation.

“Sizing those rounds is something that a lot of entrepreneurs don't have experience with and, truthfully, a lot of venture investors don't either. If you're a venture investor and you've never developed a project, if you don't have battle scars, it's hard to see all the bumps in the road,” Aaron Ratner, co-founder of Climate Risk Partners and Vectr Carbon Partners, told us.

With little precedent for climate tech projects beyond solar and wind, developers are hard-pressed to find base estimates, IRRs, or best practices. While companies and developers building in the same industries would benefit from sharing KPIs and key learnings, competing interests and still-nascent supply chains can muddy the waters.

Competing interests: “Most of these startups, what they own is their intellectual property (IP) and that's why investors invest,” Lovan said. “As an engineering company helping a lot of these startups, we are held to strict confidentiality with each one of these projects. Obviously, we have inherent learnings with every project that we do. But we're not able to say, ‘hey, we did this for this client, and this is what worked.’”

On top of novel tech and processes, there is a tremendous amount of IP startups gain from developing an actual project. While some industries are beginning to share certain insights among competitors, climate tech companies will need to lean on each other more in order for entire sectors to be successful, Lovan said.

Equipment standardization: Early climate tech projects often require customized, bespoke solutions and equipment necessary for production. And bespoke almost always equals expensive.

Shifting towards more equipment standardization or maximizing off-the-shelf components means lower costs and less time spent waiting for specialized parts. It’s another lever for de-risking projects as well, since manufacturers at-scale can give performance guarantees which ensure a certain level of equipment quality and performance and provide a layer of protection in case of equipment failure or malfunction.

For other project development KPI wish list items, we surveyed a host of developers, investors, and innovators.

✅ Transparency around regulatory processes. How long did it take for other companies to receive permits? What’s the true status of a project in the interconnection queue? How often did companies meet with regulators?

✅ Size of scale-up history. What were the number of runs and minutes per run at each stage of scale up? How did installation costs scale?

✅ Costs (expected and unexpected). What was the delivered cost per unit of capacity? How did estimated and actual project cost and timing differ across development? What are the impacts of inflation on materials, labor, and shipping?

✅ Financing requirements and structures. What percent of Seed through Series B rounds were spent on funding projects vs tech development? What project financing structures exist and what are the bankability requirements? How do tax credits transferability markets work?

✅ Community engagement. How should community stakeholders be engaged? What FAQs or informational documents should be available to external stakeholders?

Many founders and venture investors are very smart when it comes to the tech, but have little experience with project deployment—and you need both to scale up climate tech.

“There's siting, permitting, utility interconnects, geotechnical work—all sorts of stuff that needs to get in that early engineering process. And there's no way a startup has all of those skills in house,” Ratner said.

This is where a project developer would typically come in, but some climate tech startups are opting to manage their own projects.

In sectors like biogas, clean hydrogen, carbon capture, and alternative proteins, not many developers have the necessary experience either. Plus, big developers and EPC firms have plenty of work in de-risked infrastructure projects and may not want to weather the uncertainty or potential losses of taking on a smaller project with less mature tech.

Over the last century, many developers became skilled at building the same types of energy infrastructure projects and passed that knowledge on to the people who came after them. With hundreds of projects to point to for assets like midstream oil and gas, coal-fired power plants, natural-gas fired power plants, execution became fairly routine.

“What's happened over the past ~15 years is you've had this amazing transition occur at lightning speed,” Ben Hubbard, CEO of Nexus PMG, told us. “Now you're in these weird, funky asset classes, where there's agricultural things that are being processed, that are changing, depending on what you get from day to day. You've got biomass, which has moisture content swings and different species that can impact the conversion process. You've got RNG, which is a living, breathing, anaerobic digester process, and it has to be managed accordingly. It's a very different world.”

The learnings and resources to get developers up-to-speed simply don’t exist yet. And many development teams still don’t have the right mix of experience for these projects, leaning either too much on finance backgrounds with limited construction practice or too much on engineering backgrounds with limited knowledge of financing structures.

“The inexperience, to not have references to point to or 100 plants that have worked, in combination with these unbalanced teams—you're just seeing a lot of broken projects and broken deals,” Hubbard said.

The project developer then hires an EPC to help with the planning, make sure materials are ordered, and oversee the actual construction.

If you can find a good project development partner, the structure of the agreements you make can have a significant impact on the working relationship between startup/developer and EPC firm.

Traditionally, EPCs have offered fixed-price, turnkey contracts. The tech provider or developer agrees to pay a set amount for all of the work from engineering assessments through construction. The problem is that this type of contract can incentivize EPCs to cut corners in order to pocket more of that total payout.

“Everybody's trying to maximize their upside once that contract is signed,” Hubbard said.

Choosing an EPC and defining the terms of working together with them is based on identifying and assessing risk. Other types of contracts can distribute risk differently and organize profit sharing in a way that aligns incentives across developers and EPCs.

But these fixed-price agreements are what investors prefer—and often the only type they’ll underwrite—even as inflation and supply chain volatility drive EPCs to shy away from them.

There is a growing need for more project finance expertise across the climate tech sector to get projects funded, as we’ve covered previously, but there’s also a shortage of people to actually build the infrastructure.

The good news is there are more developers today who have a lot of experience raising the money for a project and executing on construction, if not deep knowledge of these specific technologies. And the recent wave of tech layoffs is driving a new pool of talent into climate sectors.

Still, it’s not necessarily more software engineers—or their Silicon Valley salaries—that climate tech companies will need as they mature. There’s a shortage of electricians and electrical engineers. There’s massive retraining that needs to take place to give workers the skills they need to operate new facilities for tech like carbon capture or waste-to-heat.

Your founding city might not be your final city: Once startups are working toward building facilities and manufacturing goods, it might make more sense to relocate to places like Detroit or Houston that have embedded infrastructure.

“There's a lot for us to learn from traditional energy infrastructure, from the oil and gas industry and other heavy industrial facilities—places that have this talent and understanding of the enabling infrastructure,” Janice Tran, CEO and co-founder of Kanin Energy, told us. “The scale-up city that you grow in may not be the city that you start in.”

Tran founded Kanin in San Francisco, but relocated the company to Houston because of the O&G knowledge base and infrastructure in the region.

The processing of scaling is going to include failures, and there needs to be some room to learn from them.

“The first iteration is not going to be the final product,” Lovan said.

Plus, even the smartest teams and the most meticulous planning won’t remove the large potential for human error once construction starts. With so many factors—from interest rate variability to supply costs—outside the control of tech innovators, cascading complexities can cause a breakdown of trust between startups, investors, and developers.

People underestimate how expensive it is to be off by just a little bit when building something, but these FOAK and early projects—by nature—will need space for failures and tweaking.

“What I, and Nexus PMG, have been doing for years is trying to educate our investor clients on how it really works,” Hubbard said. “To rethink and reimagine and adapt your contracting philosophy, your budgeting philosophy, your risk philosophy, your contingency philosophy around how things work in the real world, not how things seemingly work on a piece of paper. Because it just doesn't go that way.”

ICYMI, this is the third installment in our series on climate tech project development. Check out our other deeps dives:

Questions or comments about what we covered or what we missed in this post? Reach out at [email protected]

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs

Get the data, insights, and case studies behind the next wave of climate tech

What we heard at the Davos of Distributed Energy Resources