🌏 A tour of China's electrostate

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs

Part II: The funding hurdle for deploying emerging climate tech projects

The race to net zero is a race to deploy. Climate tech is launching off the starting block and out of the lab, but the route ahead won’t travel the same for all technology companies. For solar and wind, interconnection is currently the key bottleneck. But when it comes to deploying climate tech that’s riskier and less mature, the first cut is the deepest: how to pay for it.

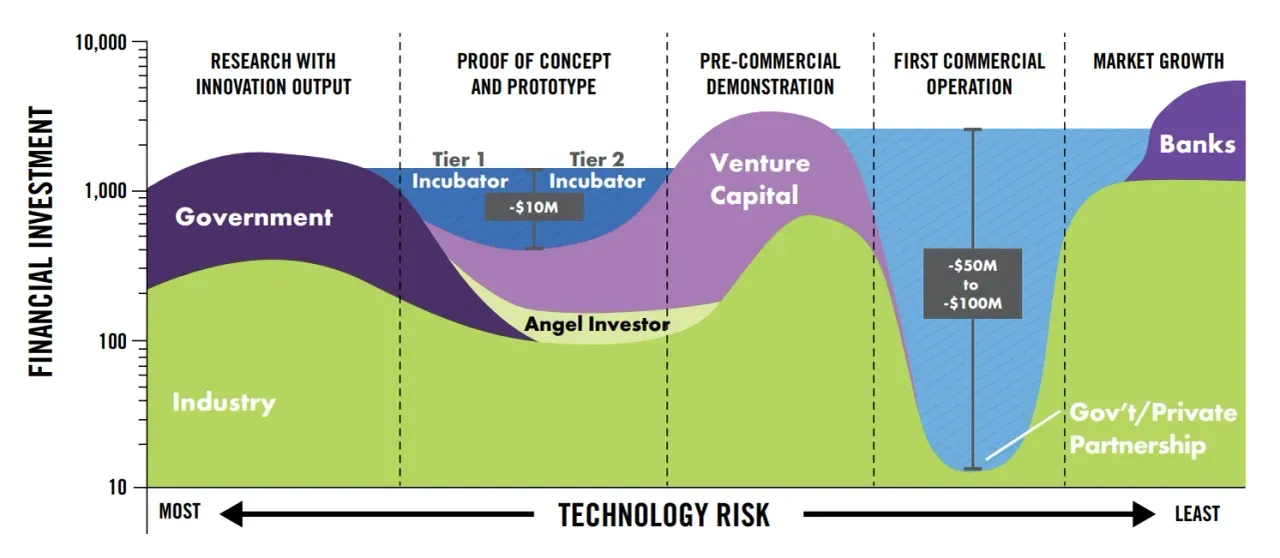

Initial steps to commercialize emerging technologies like clean hydrogen, carbon capture, long-duration storage, waste-to-value, and advanced nuclear are capital-intensive—and risky. Unsurprisingly, not many investors are jumping out of their seats to fund these first-of-a-kind (FOAK) projects.

It’s a gap that project finance has bridged in other industries building expensive physical assets and infrastructure, but until climate tech companies can meet the risk/return profile these investors are looking for (i.e., reaching bankability), the sector has limited options.

Project finance typically funds the construction phase of a single large-scale asset, like an industrial facility or power plant, by raising a combination of debt and equity funding through a separate entity called a special purpose vehicle (SPV). The SPV then takes on the project and the financing, which is usually based on projected cash flows generated by the project itself—not the creditworthiness of its sponsors or participants. Because of that separation, project finance allows earlier-stage companies to gain access to capital markets reserved for more mature borrowers.

The entities involved in a project finance transaction include lenders, like commercial banks, and equity investors, which could include the project sponsors (aka developers) themselves, private equity firms, and institutional investors. All these stakeholders work together to finance the project.

While banks and other investors might be talking about tech like carbon capture, hydrogen, or geothermal, there still isn’t a lot of capital actually moving into those sorts of projects. Venture capital is a high-risk, high-return game, but project finance is suited for assets generating high-certainty, low-risk, long-term cash flows, making it difficult for many climate tech companies to fit the profile.

The tech itself may still be relatively unproven. Offtake demand may not be sufficient. You could successfully complete a project and secure buyers only to run into regulatory or political barriers. Returns on capital only materialize if you can overcome all of these challenges. The project finance risk/return ratio is a carefully balanced equation where funding projects for unproven technologies often doesn’t pencil out.

There are key risk variables that can be mitigated to balance the math. Creating structures to back the buildout of these physical assets means de-risking everything that can be de-risked.

There’s a queue of new tech—geothermal, clean hydrogen, carbon capture, long duration energy storage, to name a few—that needs to be commercialized as we race to 2030 and 2050 net zero goals. That time crunch is also coinciding with significant economic headwinds that make debt more expensive.

The higher interest rate environment isn’t a problem specific to climate tech, but it does make it more difficult for these riskier projects to secure debt financing. The collapse of SVB also wiped out a lender with a project finance team focused on creating structures that supported climate tech (though mostly solar).

“How can we create a bridge to bankability and help technologies cross more safely on to the other side?” Caroline McGeough, operating partner at Energy Impact Partners, said. “Instead of having to go through the valley of death, give companies a whole set of stepping stones that they can complete and then graduate to that level where they get to see scale adoption.”

You have a climate tech company that needs to put its solution to the test. You’ve raised a Seed or Series A round, but now you need the capital to build at a scale that allows you to prove your product outside of the lab. Where do you turn?

Philanthropic or concessionary capital, whether through grants, firms like Breakthrough Energy Catalyst, or accelerator programs, can help meet that need for funding.

While concessionary funding can be catalytic, it isn’t always available. Grants can take a long time to secure and are often a one-time source of capital—after that, the training wheels have to come off.

This is not to say VCs aren’t providing any funding for emerging climate technologies.

Some climate tech companies are raising larger and larger early funding rounds in order to build on their own balance sheet. But how much those massive raises were enabled by a bullish market is TBD and there are some drawbacks to this route.

The DOE's Loan Programs Office is one existing alternative. With $390B to back large-scale energy projects, Jigar Shah and the LPO team are shepherding companies across this funding gap by vetting risk for federal debt capital through a process that often gives commercial lenders the peace of mind to provide follow-on funding.

Beyond grants, VCs, and government loans, there aren’t many financing structures available to climate tech companies embarking on a scale-up project. But there are a few solutions in the works.

The case for a FOAK-focused fund: Capital allocators could combine elements of private equity, infrastructure investing, and VC strategies to raise funds specifically for portfolio companies that need to build their first commercial projects.

More credit: Some large asset managers are creating funds that target companies looking to scale.

Corporate support: In the meantime, some large companies and utilities are leaning into this space—becoming customers who are also taking on a portion of the scaling risks by helping to finance projects.

Even if a customer doesn’t want to play an investor role, having long-term offtake agreements with established companies in place goes a long way.

The lack of project financing experience on both the founder and investor sides is further hindering early stage climate tech companies.

It's not uncommon for tech startups to get crippled early on because the experts in the C-suite all come from science backgrounds. Even startup leaders with business experience may not understand how to work within project finance models. “If you can't speak the language, you are at a huge step back,” Li said.

At the same time, some investors are dipping their toes into more emerging climate tech, but don’t have the same robust strategies for solutions like clean hydrogen or carbon capture that they do for renewables.

While there are resources in VC to teach entrepreneurs how to raise capital, the same doesn’t exist for project finance models. The best alternative is having someone on staff with experience—cue the surge in frantic open job descriptions for “strategic finance” roles at growing climate tech companies.

On top of that inexperience, these sectors are still testing what works best, so there aren’t yet agreed-upon metrics to describe risk levels. Even as those definitions become more concrete, they won’t be uniform across different technologies.

Without clear indicators of risk,

The project finance model, which decouples the risk of developing a project from the entity building it, has enabled the construction of scores of power-generating assets, highways, factories, pipelines, mines, and telecoms infrastructure.

This debt capital comes at a lower cost than VC dollars and brings teams that have experience deploying projects at scale. But, generally, project financiers aren’t ready to step into climate tech and take on the risk that comes with a still-nascent sector.

Investors in large infrastructure projects break down the risks and address each category separately:

Insurance providers lead the way for lenders, so climate tech will need new policies in order to reach bankability.

“The way that the current oil and gas infrastructure was built out, it was all with credit and insurance. There is no such thing as credit without an insurance policy in place, because lenders are just risk averse,” Ratner said.

Although the world of insurance may sound stuffy and dated, this could be one area ripe for innovation, Ratner argues, especially in managing risk for early offtakers. For example, some newer policy options aim to make customers whole if climate tech suppliers experience hiccups.

Getting creative with tax and environmental credits could be another useful lever for early-stage climate tech.

Behind all of these projects are people—just not enough of them. Solving this bottleneck is not only about having more available capital and more manageable risks, but also more people to assess deals and cut checks.

Recruit from other industries: Climate tech founders may not have project development experience, but plenty of people working at large corporates do. To quickly add skill sets needed to execute (e.g., project management, stakeholder communication, vendor and offtaker contract negotiation, procurement, project budget management, etc.) that are likely outside the wheelhouse of a startup team, look to bring in talent from other industries.

Follow the solar model: Solar projects have become the climate tech standard. With a fairly uniform understanding of the cash flows and the methods of underwriting for solar, investors don’t have to do as much work to vet the credit worthiness of individual projects.

Standardize offtake contracts: Climate tech companies should also aim to standardize their PPAs, McGeough said. That’s difficult at first—when startups have to meet the needs of any potential large clients and may still be trying to target multiple end users for their products—but can make these agreements less time-consuming in the long run.

A big thank you to Deanna Zhang, Alyssa Spagnolo, and Kobi Weinberg for sharing their insights and structuring our thoughts on funding climate tech projects.

ICYMI, this is the second installment in our series on climate tech project development. Check out our other deeps dives:

Questions or comments about what we covered or what we missed in this post? Reach out at [email protected]

My visit to China's cleantech factories, labs, and HQs

Get the data, insights, and case studies behind the next wave of climate tech

What we heard at the Davos of Distributed Energy Resources