🌍 Getting current on kelp processing with Macro Oceans

The synthetic bio startup sees an upswell of seaweed applications beyond the food industry

This week we dig into one of the oldest (but most complex) carbon removal pathways in the book – soil.

Sometimes it’s the simplest solutions that can be the most challenging. Last week we wrote about technologies to engineer new pathways for capturing atmospheric carbon. This week we dig into one of the oldest (but most complex) carbon removal pathways in the book – soil.

While society has perfected the business of extracting carbon from the ground, only recently have scientists, entrepreneurs, and corporates seriously attempted to reverse the conveyor belt and increase the carbon stored in soils. But contenders have the shot off the starting blocks. Just last week, Microsoft announced the purchase of just under 200,000 mtCO2 from two soil projects (Truterra/Land O’Lakes and Regen Network) and Biden’s climate executive orders encouraged “climate-smart agricultural practices that produce verifiable carbon reductions and sequestrations.” The potential prize is big: scientists estimate nearly 500 gigatons of CO2 equivalents have been eroded from soils.

The existing voluntary offset market where corporates can buy credits as “currency” to counterbalance their emissions is increasingly offering soil carbon as a new flavor of offset product. While forestry-based carbon offsets are relatively plentiful, regenerative ag and forestry make up just 2% of the market. Australia boasts the most robust soil carbon market with an established government-backed marketplace and a regulated, empirical measurement methodology.

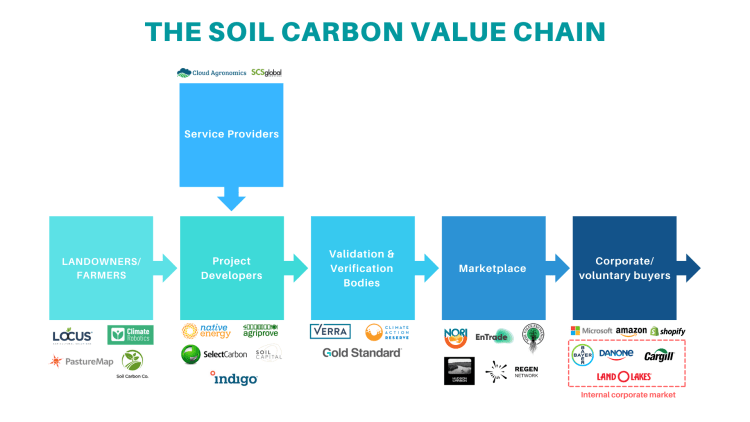

Nature-based climate solutions are accelerating as a critical strategy to reach net-zero (as Mark Tercek well articulates). On top of their sequestration benefits, healthy soils mutually benefit farm productivity. Despite the increasing enthusiasm and obvious benefits, a number of questions remain about the viability of soil carbon sequestration: What tools can farmers use? How accurately can we monitor and quantify? What is the right market or policy structure to reward farmers and enable scaling? A number of entrepreneurs (many of which were featured in IndigoAg’s Carbon Challenge last week) are hard at work developing solutions to these questions. We spoke to some of these founders, soil scientists, and investors to unearth this complex value chain.

It takes growers’ boots on the ground to adopt effective carbon-sequestering regenerative management practices like no-till, planting cover and mixed species forage crops, rotational livestock grazing, conversion of cropland to pasture, and reduced chemical use. Startups like Climate Robotics and Soil Carbon offer a further carbon retention boost with their respective biochar and microbial products. From a farmers’ P&L perspective, carbon-rich healthy soils mean good business not only from diversified carbon credit income, but importantly also from reduced soil erosion, lower chemical inputs, and improved biodiversity.

In response to early criticism, carbon credit methodologies have increased in rigor. While significant discussion remains, all carbon projects must now prove realness, completeness, consistency, transparency, additionality, etc. Project developers (e.g., NativeEnergy, AgriProve, Soil Capital) handle this complexity and are on the hook with auditors. Matthew Warnken, Managing Director of AgriProve, explains “we provide a one-stop shop to agricultural landholders in managing the administrative, monitoring, reporting, and compliance requirements of soil carbon projects, freeing the landholders to focus on the land management practice change for soil carbon.”

By closely adhering to a third party registry’s (e.g. Verra, CAR) methodology, project developers design projects and then act as the middle broker by supporting and partnering with farmers. First, project developers register a soil carbon project, then the area undergoes a baseline soil sample test, next the landholder or farmer undertakes regenerative practices with the goal of sequestering carbon. 1-5 years later, the area is sampled again to measure a creditable increase in soil organic carbon stocks. Only then are verified carbon credits awarded.

Undertaking sequestering practices is no longer enough to claim credible carbon credits. Rigorous measurement, reporting, and verification are crucial to scale demand for soil carbon credits. Currently, one needed a literal hammer and steel to extract physical soil cores which were then mailed to a lab and incinerated to determine organic carbon content. Emerging technology companies using in-situ spectrometry (Yard Stick, currently in stealth) and AI-enabled remote sensing (Cloud Agronomics) are bringing down the cost and time curves in order to scale MRV.

Cloud Agronomics combines remote sensing with artificial intelligence to remotely measure soil organic carbon levels in farmland. By combining attributes of the soil, AI, satellite imagery and ground truth soil sampling, the company is able to detect carbon levels up to 30cm underground. CEO Mark Tracy explains, “If you use traditional soil sampling, you can’t capture in-field variability well. We are providing the same quantifiable information, but we can aggregate thousands of points within a field to come to an accurate value for that entire field, not just single points.”

Project developers can sell the carbon credits they produced to a variety of players:

Special thanks to Stella Liu for helping us unearth the dirt on soil carbon sequestration.

Interested in more content like this? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter on Climate Tech below!

The synthetic bio startup sees an upswell of seaweed applications beyond the food industry

A gut check on reducing bovine burps

The underappreciated role of carbon insets in decarbonizing Scope 3 supply chains